NOW AFTER all these things had happened, and it became known to Robin Hood how the Sheriff had tried three times to make him captive, he said to himself, “If I have the chance, I will make our worshipful Sheriff pay right well for that which he hath done to me. Maybe I may bring him some time into Sherwood Forest and have him to a right merry feast with us.” For when Robin Hood caught a baron or a squire, or a fat abbot or bishop, he brought them to the greenwood tree and feasted them before he lightened their purses.

But in the meantime Robin Hood and his band lived quietly in Sherwood Forest, without showing their faces abroad, for Robin knew that it would not be wise for him to be seen in the neighborhood of Nottingham, those in authority being very wroth with him. But though they did not go abroad, they lived a merry life within the woodlands, spending the days in shooting at garlands hung upon a willow wand at the end of the glade, the leafy aisles ringing with merry jests and laughter: for whoever missed the garland was given a sound buffet, which, if delivered by Little John, never failed to topple over the unfortunate yeoman. Then they had bouts of wrestling and of cudgel play, so that every day they gained in skill and strength.

Thus they dwelled for nearly a year, and in that time Robin Hood often turned over in his mind many means of making an even score with the Sheriff. At last he began to fret at his confinement; so one day he took up his stout cudgel and set forth to seek adventure, strolling blithely along until he came to the edge of Sherwood. There, as he rambled along the sunlit road, he met a lusty young butcher driving a fine mare and riding in a stout new cart, all hung about with meat. Merrily whistled the Butcher as he jogged along, for he was going to the market, and the day was fresh and sweet, making his heart blithe within him.

“Good morrow to thee, jolly fellow,” quoth Robin, “thou seemest happy this merry morn.”

“Ay, that am I,” quoth the jolly Butcher, “and why should I not be so? Am I not hale in wind and limb? Have I not the bonniest lass in all Nottinghamshire? And lastly, am I not to be married to her on Thursday next in sweet Locksley Town?”

“Ha,” said Robin, “comest thou from Locksley Town? Well do I know that fair place for miles about, and well do I know each hedgerow and gentle pebbly stream, and even all the bright little fishes therein, for there I was born and bred. Now, where goest thou with thy meat, my fair friend?”

“I go to the market at Nottingham Town to sell my beef and my mutton,” answered the Butcher. “But who art thou that comest from Locksley Town?”

“A yeoman am I, and men do call me Robin Hood.”

“Now, by Our Lady’s grace,” cried the Butcher, “well do I know thy name, and many a time have I heard thy deeds both sung and spoken of. But Heaven forbid that thou shouldst take aught of me! An honest man am I, and have wronged neither man nor maid; so trouble me not, good master, as I have never troubled thee.”

“Nay, Heaven forbid, indeed,” quoth Robin, “that I should take from such as thee, jolly fellow! Not so much as one farthing would I take from thee, for I love a fair Saxon face like thine right well—more especially when it cometh from Locksley Town, and most especially when the man that owneth it is to marry a bonny lass on Thursday next. But come, tell me for what price thou wilt sell me all of thy meat and thy horse and cart.”

“At four marks do I value meat, cart, and mare,” quoth the Butcher, “but if I do not sell all my meat I will not have four marks in value.”

Then Robin Hood plucked the purse from his girdle, and quoth he, “Here in this purse are six marks. Now, I would fain be a butcher for the day and sell my meat in Nottingham Town. Wilt thou close a bargain with me and take six marks for thine outfit?”

“Now may the blessings of all the saints fall on thine honest head!” cried the Butcher right joyfully, as he leaped down from his cart and took the purse that Robin held out to him.

“Nay,” quoth Robin, laughing loudly, “many do like me and wish me well, but few call me honest. Now get thee gone back to thy lass, and give her a sweet kiss from me.” So saying, he donned the Butcher’s apron, and, climbing into the cart, he took the reins in his hand and drove off through the forest to Nottingham Town.

When he came to Nottingham, he entered that part of the market where butchers stood, and took up his inn[Stand for selling] in the best place he could find. Next, he opened his stall and spread his meat upon the bench, then, taking his cleaver and steel and clattering them together, he trolled aloud in merry tones:

| “Now come, ye lasses, and eke ye dames, And buy your meat from me; For three pennyworths of meat I sell For the charge of one penny. “Lamb have I that hath fed upon nought But the dainty dames pied, And the violet sweet, and the daffodil That grow fair streams beside. “And beef have I from the heathery words, And mutton from dales all green, And veal as white as a maiden’s brow, With its mother’s milk, I ween. “Then come, ye lasses, and eke ye dames, Come, buy your meat from me, For three pennyworths of meat I sell For the charge of one penny.” |

Thus he sang blithely, while all who stood near listened amazedly. Then, when he had finished, he clattered the steel and cleaver still more loudly, shouting lustily, “Now, who’ll buy? Who’ll buy? Four fixed prices have I. Three pennyworths of meat I sell to a fat friar or priest for sixpence, for I want not their custom; stout aldermen I charge threepence, for it doth not matter to me whether they buy or not; to buxom dames I sell three pennyworths of meat for one penny for I like their custom well; but to the bonny lass that hath a liking for a good tight butcher I charge nought but one fair kiss, for I like her custom the best of all.”

Then all began to stare and wonder and crowd around, laughing, for never was such selling heard of in all Nottingham Town; but when they came to buy they found it as he had said, for he gave goodwife or dame as much meat for one penny as they could buy elsewhere for three, and when a widow or a poor woman came to him, he gave her flesh for nothing; but when a merry lass came and gave him a kiss, he charged not one penny for his meat; and many such came to his stall, for his eyes were as blue as the skies of June, and he laughed merrily, giving to each full measure. Thus he sold his meat so fast that no butcher that stood near him could sell anything.

Then they began to talk among themselves, and some said, “This must be some thief who has stolen cart, horse, and meat”; but others said, “Nay, when did ye ever see a thief who parted with his goods so freely and merrily? This must be some prodigal who hath sold his father’s land, and would fain live merrily while the money lasts.” And these latter being the greater number, the others came round, one by one to their way of thinking.

Then some of the butchers came to him to make his acquaintance. “Come, brother,” quoth one who was the head of them all, “we be all of one trade, so wilt thou go dine with us? For this day the Sheriff hath asked all the Butcher Guild to feast with him at the Guild Hall. There will be stout fare and much to drink, and that thou likest, or I much mistake thee.”

“Now, beshrew his heart,” quoth jolly Robin, “that would deny a butcher. And, moreover, I will go dine with you all, my sweet lads, and that as fast as I can hie.” Whereupon, having sold all his meat, he closed his stall and went with them to the great Guild Hall.

There the Sheriff had already come in state, and with him many butchers. When Robin and those that were with him came in, all laughing at some merry jest he had been telling them, those that were near the Sheriff whispered to him, “Yon is a right mad blade, for he hath sold more meat for one penny this day than we could sell for three, and to whatsoever merry lass gave him a kiss he gave meat for nought.” And others said, “He is some prodigal that hath sold his land for silver and gold, and meaneth to spend all right merrily.”

Then the Sheriff called Robin to him, not knowing him in his butcher’s dress, and made him sit close to him on his right hand; for he loved a rich young prodigal—especially when he thought that he might lighten that prodigal’s pockets into his own most worshipful purse. So he made much of Robin, and laughed and talked with him more than with any of the others.

At last the dinner was ready to be served and the Sheriff bade Robin say grace, so Robin stood up and said, “Now Heaven bless us all and eke good meat and good sack within this house, and may all butchers be and remain as honest men as I am.”

At this all laughed, the Sheriff loudest of all, for he said to himself, “Surely this is indeed some prodigal, and perchance I may empty his purse of some of the money that the fool throweth about so freely.” Then he spake aloud to Robin, saying, “Thou art a jolly young blade, and I love thee mightily”; and he smote Robin upon the shoulder.

Then Robin laughed loudly too. “Yea,” quoth he, “I know thou dost love a jolly blade, for didst thou not have jolly Robin Hood at thy shooting match and didst thou not gladly give him a bright golden arrow for his own?”

At this the Sheriff looked grave and all the guild of butchers too, so that none laughed but Robin, only some winked slyly at each other.

“Come, fill us some sack!” cried Robin. “Let us e’er be merry while we may, for man is but dust, and he hath but a span to live here till the worm getteth him, as our good gossip Swanthold sayeth; so let life be merry while it lasts, say I. Nay, never look down i’ the mouth, Sir Sheriff. Who knowest but that thou mayest catch Robin Hood yet, if thou drinkest less good sack and Malmsey, and bringest down the fat about thy paunch and the dust from out thy brain. Be merry, man.”

Then the Sheriff laughed again, but not as though he liked the jest, while the butchers said, one to another, “Before Heaven, never have we seen such a mad rollicking blade. Mayhap, though, he will make the Sheriff mad.”

“How now, brothers,” cried Robin, “be merry! nay, never count over your farthings, for by this and by that I will pay this shot myself, e’en though it cost two hundred pounds. So let no man draw up his lip, nor thrust his forefinger into his purse, for I swear that neither butcher nor Sheriff shall pay one penny for this feast.”

“Now thou art a right merry soul,” quoth the Sheriff, “and I wot thou must have many a head of horned beasts and many an acre of land, that thou dost spend thy money so freely.”

“Ay, that have I,” quoth Robin, laughing loudly again, “five hundred and more horned beasts have I and my brothers, and none of them have we been able to sell, else I might not have turned butcher. As for my land, I have never asked my steward how many acres I have.”

At this the Sheriff’s eyes twinkled, and he chuckled to himself. “Nay, good youth,” quoth he, “if thou canst not sell thy cattle, it may be I will find a man that will lift them from thy hands; perhaps that man may be myself, for I love a merry youth and would help such a one along the path of life. Now how much dost thou want for thy horned cattle?”

“Well,” quoth Robin, “they are worth at least five hundred pounds.”

“Nay,” answered the Sheriff slowly, and as if he were thinking within himself, “well do I love thee, and fain would I help thee along, but five hundred pounds in money is a good round sum; besides I have it not by me. Yet I will give thee three hundred pounds for them all, and that in good hard silver and gold.”

“Now thou old miser!” quoth Robin, “well thou knowest that so many horned cattle are worth seven hundred pounds and more, and even that is but small for them, and yet thou, with thy gray hairs and one foot in the grave, wouldst trade upon the folly of a wild youth.”

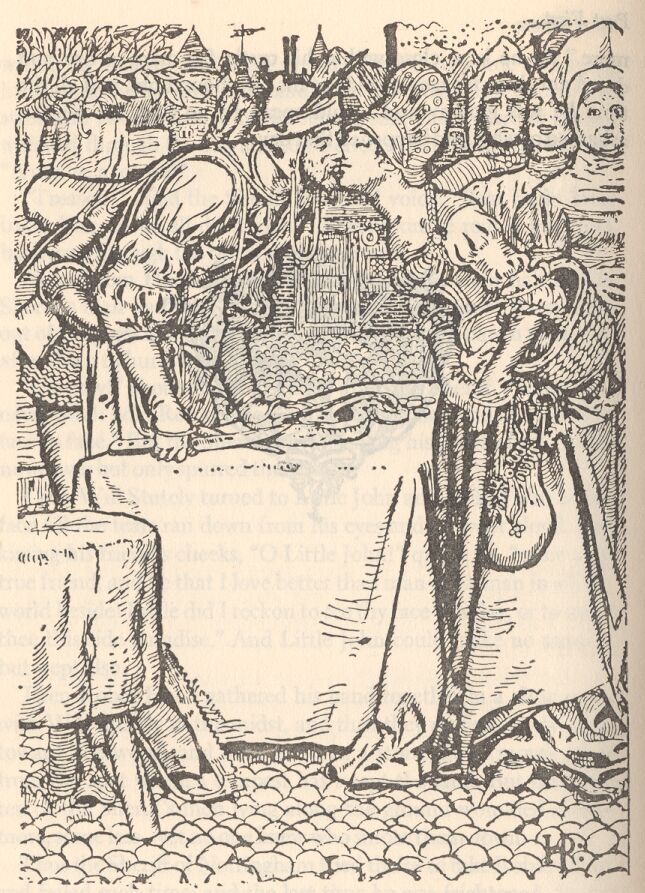

At this the Sheriff looked grimly at Robin. “Nay,” quoth Robin, “look not on me as though thou hadst sour beer in thy mouth, man. I will take thine offer, for I and my brothers do need the money. We lead a merry life, and no one leads a merry life for a farthing, so I will close the bargain with thee. But mind that thou bringest a good three hundred pounds with thee, for I trust not one that driveth so shrewd a bargain.”

“I will bring the money,” said the Sheriff. “But what is thy name, good youth?”

“Men call me Robert o’ Locksley,” quoth bold Robin.

“Then, good Robert o’ Locksley,” quoth the Sheriff, “I will come this day to see thy horned beasts. But first my clerk shall draw up a paper in which thou shalt be bound to the sale, for thou gettest not my money without I get thy beasts in return.”

Then Robin Hood laughed again. “So be it,” he said, smiting his palm upon the Sheriff’s hand. “Truly my brothers will be thankful to thee for thy money.”

Thus the bargain was closed, but many of the butchers talked among themselves of the Sheriff, saying that it was but a scurvy trick to beguile a poor spendthrift youth in this way.

The afternoon had come when the Sheriff mounted his horse and joined Robin Hood, who stood outside the gateway of the paved court waiting for him, for he had sold his horse and cart to a trader for two marks. Then they set forth upon their way, the Sheriff riding upon his horse and Robin running beside him. Thus they left Nottingham Town and traveled forward along the dusty highway, laughing and jesting together as though they had been old friends. But all the time the Sheriff said within himself, “Thy jest to me of Robin Hood shall cost thee dear, good fellow, even four hundred pounds, thou fool.” For he thought he would make at least that much by his bargain.

So they journeyed onward till they came within the verge of Sherwood Forest, when presently the Sheriff looked up and down and to the right and to the left of him, and then grew quiet and ceased his laughter. “Now,” quoth he, “may Heaven and its saints preserve us this day from a rogue men call Robin Hood.”

Then Robin laughed aloud. “Nay,” said he, “thou mayst set thy mind at rest, for well do I know Robin Hood and well do I know that thou art in no more danger from him this day than thou art from me.”

At this the Sheriff looked askance at Robin, saying to himself, “I like not that thou seemest so well acquainted with this bold outlaw, and I wish that I were well out of Sherwood Forest.”

But still they traveled deeper into the forest shades, and the deeper they went, the more quiet grew the Sheriff. At last they came to where the road took a sudden bend, and before them a herd of dun deer went tripping across the path. Then Robin Hood came close to the Sheriff and pointing his finger, he said, “These are my horned beasts, good Master Sheriff. How dost thou like them? Are they not fat and fair to see?”

At this the Sheriff drew rein quickly. “Now fellow,” quoth he, “I would I were well out of this forest, for I like not thy company. Go thou thine own path, good friend, and let me but go mine.”

But Robin only laughed and caught the Sheriff’s bridle rein. “Nay,” cried he, “stay awhile, for I would thou shouldst see my brothers, who own these fair horned beasts with me.” So saying, he clapped his bugle to his mouth and winded three merry notes, and presently up the path came leaping fivescore good stout yeomen with Little John at their head.

“What wouldst thou have, good master?” quoth Little John.

“Why,” answered Robin, “dost thou not see that I have brought goodly company to feast with us today? Fye, for shame! Do you not see our good and worshipful master, the Sheriff of Nottingham? Take thou his bridle, Little John, for he has honored us today by coming to feast with us.”

Then all doffed their hats humbly, without smiling or seeming to be in jest, while Little John took the bridle rein and led the palfrey still deeper into the forest, all marching in order, with Robin Hood walking beside the Sheriff, hat in hand.

All this time the Sheriff said never a word but only looked about him like one suddenly awakened from sleep; but when he found himself going within the very depths of Sherwood his heart sank within him, for he thought, “Surely my three hundred pounds will be taken from me, even if they take not my life itself, for I have plotted against their lives more than once.” But all seemed humble and meek and not a word was said of danger, either to life or money.

So at last they came to that part of Sherwood Forest where a noble oak spread its branches wide, and beneath it was a seat all made of moss, on which Robin sat down, placing the Sheriff at his right hand. “Now busk ye, my merry men all,” quoth he, “and bring forth the best we have, both of meat and wine, for his worship the Sheriff hath feasted me in Nottingham Guild Hall today, and I would not have him go back empty.”

All this time nothing had been said of the Sheriff’s money, so presently he began to pluck up heart. “For,” said he to himself, “maybe Robin Hood hath forgotten all about it.”

Then, while beyond in the forest bright fires crackled and savory smells of sweetly roasting venison and fat capons filled the glade, and brown pasties warmed beside the blaze, did Robin Hood entertain the Sheriff right royally. First, several couples stood forth at quarterstaff, and so shrewd were they at the game, and so quickly did they give stroke and parry, that the Sheriff, who loved to watch all lusty sports of the kind, clapped his hands, forgetting where he was, and crying aloud, “Well struck! Well struck, thou fellow with the black beard!” little knowing that the man he called upon was the Tinker that tried to serve his warrant upon Robin Hood.

Then several yeomen came forward and spread cloths upon the green grass, and placed a royal feast; while others still broached barrels of sack and Malmsey and good stout ale, and set them in jars upon the cloth, with drinking horns about them. Then all sat down and feasted and drank merrily together until the sun was low and the half-moon glimmered with a pale light betwixt the leaves of the trees overhead.

Then the Sheriff arose and said, “I thank you all, good yeomen, for the merry entertainment ye have given me this day. Right courteously have ye used me, showing therein that ye have much respect for our glorious King and his deputy in brave Nottinghamshire. But the shadows grow long, and I must away before darkness comes, lest I lose myself within the forest.”

Then Robin Hood and all his merry men arose also, and Robin said to the Sheriff, “If thou must go, worshipful sir, go thou must; but thou hast forgotten one thing.”

“Nay, I forgot nought,” said the Sheriff; yet all the same his heart sank within him.

“But I say thou hast forgot something,” quoth Robin. “We keep a merry inn here in the greenwood, but whoever becometh our guest must pay his reckoning.”

Then the Sheriff laughed, but the laugh was hollow. “Well, jolly boys,” quoth he, “we have had a merry time together today, and even if ye had not asked me, I would have given you a score of pounds for the sweet entertainment I have had.”

“Nay,” quoth Robin seriously, “it would ill beseem us to treat Your Worship so meanly. By my faith, Sir Sheriff, I would be ashamed to show my face if I did not reckon the King’s deputy at three hundred pounds. Is it not so, my merry men all?”

Then “Ay!” cried all, in a loud voice.

“Three hundred devils!” roared the Sheriff. “Think ye that your beggarly feast was worth three pounds, let alone three hundred?”

“Nay,” quoth Robin gravely. “Speak not so roundly, Your Worship. I do love thee for the sweet feast thou hast given me this day in merry Nottingham Town; but there be those here who love thee not so much. If thou wilt look down the cloth thou wilt see Will Stutely, in whose eyes thou hast no great favor; then two other stout fellows are there here that thou knowest not, that were wounded in a brawl nigh Nottingham Town, some time ago—thou wottest when; one of them was sore hurt in one arm, yet he hath got the use of it again. Good Sheriff, be advised by me; pay thy score without more ado, or maybe it may fare ill with thee.”

As he spoke the Sheriff’s ruddy cheeks grew pale, and he said nothing more but looked upon the ground and gnawed his nether lip. Then slowly he drew forth his fat purse and threw it upon the cloth in front of him.

“Now take the purse, Little John,” quoth Robin Hood, “and see that the reckoning be right. We would not doubt our Sheriff, but he might not like it if he should find he had not paid his full score.”

Then Little John counted the money and found that the bag held three hundred pounds in silver and gold. But to the Sheriff it seemed as if every clink of the bright money was a drop of blood from his veins. And when he saw it all counted out in a heap of silver and gold, filling a wooden platter, he turned away and silently mounted his horse.

“Never have we had so worshipful a guest before!” quoth Robin, “and, as the day waxeth late, I will send one of my young men to guide thee out of the forest depths.”

“Nay, Heaven forbid!” cried the Sheriff hastily. “I can find mine own way, good man, without aid.”

“Then I will put thee on the right track mine own self,” quoth Robin, and, taking the Sheriff’s horse by the bridle rein, he led him into the main forest path. Then, before he let him go, he said, “Now, fare thee well, good Sheriff, and when next thou thinkest to despoil some poor prodigal, remember thy feast in Sherwood Forest. ‘Ne’er buy a horse, good friend, without first looking into its mouth,’ as our good gaffer Swanthold says. And so, once more, fare thee well.” Then he clapped his hand to the horse’s back, and off went nag and Sheriff through the forest glades.

Then bitterly the Sheriff rued the day that first he meddled with Robin Hood, for all men laughed at him and many ballads were sung by folk throughout the country, of how the Sheriff went to shear and came home shorn to the very quick. For thus men sometimes overreach themselves through greed and guile.