The chains of the rigorous regime which had bound me snapped for good when I set out from home. On my return I gained an accession of rights. In my case my very nearness had so long kept me out of mind; now that I had been out of sight I came back into view.

I got a foretaste of appreciation while still on the return journey. Travelling alone as I was, with an attendant, brimming with health and spirits, and conspicuous with my gold-worked cap, all the English people I came across in the train made much of me.

When I arrived it was not merely a home-coming from travel, it was also a return from my exile in the servants’ quarters to my proper place in the inner apartments. Whenever the inner household assembled in my mother’s room I now occupied a seat of honour. And she who was then the youngest bride of our house lavished on me a wealth of affection and regard.

In infancy the loving care of woman is to be had without the asking, and, being as much a necessity as light and air, is as simply accepted without any conscious response; rather does the growing child often display an eagerness to free itself from the encircling web of woman’s solicitude. But the unfortunate creature who is deprived of this in its proper season is beggared indeed. This had been my plight. So after being brought up in the servants’ quarters when I suddenly came in for a profusion of womanly affection, I could hardly remain unconscious of it.

In the days when the inner apartments were as yet far away from me, they were the elysium of my imagination. The zenana, which from an outside view is a place of confinement, for me was the abode of all freedom. Neither school nor Pandit were there; nor, it seemed to me, did anybody have to do what they did not want to. Its secluded leisure had something mysterious about it; one played about, or did as one liked and had not to render an account of one’s doings. Specially so with my youngest sister, to whom, though she attended Nilkamal Pandit’s class with us, it seemed to make no difference in his behaviour whether she did her lessons well or ill. Then again, while, by ten o’clock, we had to hurry through our breakfast and be ready for school, she, with her queue dangling behind, walked unconcernedly away, withinwards, tantalising us to distraction.

And when the new bride, adorned with her necklace of gold, came into our house, the mystery of the inner apartments deepened. She, who came from outside and yet became one of us, who was unknown and yet our own, attracted me strangely—with her I burned to make friends. But if by much contriving I managed to draw near, my youngest sister would hustle me off with: “What d’you boys want here—get away outside.” The insult added to the disappointment cut me to the quick. Through the glass doors of their cabinets one could catch glimpses of all manner of curious playthings—creations of porcelain and glass—gorgeous in colouring and ornamentation. We were not deemed worthy even to touch them, much less could we muster up courage to ask for any to play with. Nevertheless these rare and wonderful objects, as they were to us boys, served to tinge with an additional attraction the lure of the inner apartments.

Thus had I been kept at arm’s length with repeated rebuffs. As the outer world, so, for me, the interior, was unattainable. Wherefore the impressions of it that I did get appeared to me like pictures.

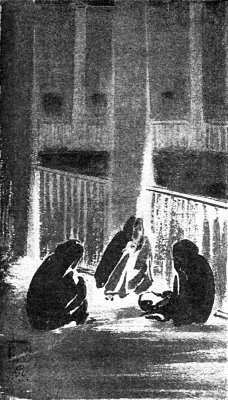

After nine in the evening, my lessons with Aghore Babu over, I am retiring within for the night. A murky flickering lantern is hanging in the long venetian-screened corridor leading from the outer to the inner apartments. At its end this passage turns into a flight of four or five steps, to which the light does not reach, and down which I pass into the galleries running round the first inner quadrangle. A shaft of moonlight slants from the eastern sky into the western angle of these verandahs, leaving the rest in darkness. In this patch of light the maids have gathered and are squatting close together, with legs outstretched, rolling cotton waste into lamp-wicks, and chatting in undertones of their village homes. Many such pictures are indelibly printed on my memory.

Then after our supper, the washing of our hands and feet on the verandah before stretching ourselves on the ample expanse of our bed; whereupon one of the nurses Tinkari or Sankari comes and sits by our heads and softly croons to us the story of the prince travelling on and on over the lonely moor, and, as it comes to an end, silence falls on the room. With my face to the wall I gaze at the black and white patches, made by the plaster of the walls fallen off here and there, showing faintly in the dim light; and out of these I conjure up many a fantastic image as I drop off to sleep. And sometimes, in the middle of the night, I hear through my half-broken sleep the shouts of old Swarup, the watchman, going his rounds from verandah to verandah.

Then came the new order, when I got in profusion from this inner unknown dreamland of my fancies the recognition for which I had all along been pining; when that which naturally should have come day by day was suddenly made good to me with accumulated arrears. I cannot say that my head was not turned.

The little traveller was full of the story of his travels, and, with the strain of each repetition, the narrative got looser and looser till it utterly refused to fit into the facts. Like everything else, alas, a story also gets stale and the glory of the teller suffers likewise; that is why he has to add fresh colouring every time to keep up its freshness.

After my return from the hills I was the principal speaker at my mother’s open air gatherings on the roof terrace in the evenings. The temptation to become famous in the eyes of one’s mother is as difficult to resist as such fame is easy to earn. While I was at the Normal School, when I first came across the information in some reader that the Sun was hundreds and thousands of times as big as the Earth, I at once disclosed it to my mother. It served to prove that he who was small to look at might yet have a considerable amount of bigness about him. I used also to recite to her the scraps of poetry used as illustrations in the chapter on prosody or rhetoric of our Bengali grammar. Now I retailed at her evening gatherings the astronomical tit-bits I had gleaned from Proctor.

My father’s follower Kishori belonged at one time to a band of reciters of Dasarathi’s jingling versions of the Epics. While we were together in the hills he often said to me: “Oh, my little brother, if I only had had you in our troupe we could have got up a splendid performance.” This would open up to me a tempting picture of wandering as a minstrel boy from place to place, reciting and singing. I learnt from him many of the songs in his repertoire and these were in even greater request than my talks about the photosphere of the Sun or the many moons of Saturn.

But the achievement of mine which appealed most to my mother was that while the rest of the inmates of the inner apartments had to be content with Krittivasa’s Bengali rendering of the Ramayana, I had been reading with my father the original of Maharshi Valmiki himself, Sanscrit metre and all. “Read me some of that Ramayana, do!” she said, overjoyed at this news which I had given her.

The Servant-maids in the Verandah

Alas, my reading of Valmiki had been limited to the short extract from his Ramayana given in my Sanskrit reader, and even that I had not fully mastered. Moreover, on looking over it now, I found that my memory had played me false and much of what I thought I knew had become hazy. But I lacked the courage to plead “I have forgotten” to the eager mother awaiting the display of her son’s marvellous talents; so that, in the reading I gave, a large divergence occurred between Valmiki’s intention and my explanation. That tender-hearted sage, from his seat in heaven, must have forgiven the temerity of the boy seeking the glory of his mother’s approbation, but not so Madhusudan, the taker down of Pride.

My mother, unable to contain her feelings at my extraordinary exploit, wanted all to share her admiration. “You must read this to Dwijendra,” (my eldest brother), she said.

“In for it!” thought I, as I put forth all the excuses I could think of, but my mother would have none of them. She sent for my brother Dwijendra, and, as soon as he arrived, greeted him, with: “Just hear Rabi read Valmiki’s Ramayan, how splendidly he does it.”

It had to be done! But Madhusudan relented and let me off with just a taste of his pride-reducing power. My brother must have been called away while busy with some literary work of his own. He showed no anxiety to hear me render the Sanscrit into Bengali, and as soon as I had read out a few verses he simply remarked “Very good” and walked away.

After my promotion to the inner apartments I felt it all the more difficult to resume my school life. I resorted to all manner of subterfuges to escape the Bengal Academy. Then they tried putting me at St. Xavier’s. But the result was no better.

My elder brothers, after a few spasmodic efforts, gave up all hopes of me—they even ceased to scold me. One day my eldest sister said: “We had all hoped Rabi would grow up to be a man, but he has disappointed us the worst.” I felt that my value in the social world was distinctly depreciating; nevertheless I could not make up my mind to be tied to the eternal grind of the school mill which, divorced as it was from all life and beauty, seemed such a hideously cruel combination of hospital and gaol.

One precious memory of St. Xavier’s I still hold fresh and pure—the memory of its teachers. Not that they were all of the same excellence. In particular, in those who taught in our class I could discern no reverential resignation of spirit. They were in nowise above the teaching-machine variety of school masters. As it is, the educational engine is remorselessly powerful; when to it is coupled the stone mill of the outward forms of religion the heart of youth is crushed dry indeed. This power-propelled grindstone type we had at St. Xavier’s. Yet, as I say, I possess a memory which elevates my impression of the teachers there to an ideal plane.

This is the memory of Father DePeneranda. He had very little to do with us—if I remember right he had only for a while taken the place of one of the masters of our class. He was a Spaniard and seemed to have an impediment in speaking English. It was perhaps for this reason that the boys paid but little heed to what he was saying. It seemed to me that this inattentiveness of his pupils hurt him, but he bore it meekly day after day. I know not why, but my heart went out to him in sympathy. His features were not handsome, but his countenance had for me a strange attraction. Whenever I looked on him his spirit seemed to be in prayer, a deep peace to pervade him within and without.

We had half-an-hour for writing our copybooks; that was a time when, pen in hand, I used to become absent-minded and my thoughts wandered hither and thither. One day Father DePeneranda was in charge of this class. He was pacing up and down behind our benches. He must have noticed more than once that my pen was not moving. All of a sudden he stopped behind my seat. Bending over me he gently laid his hand on my shoulder and tenderly inquired: “Are you not well, Tagore?” It was only a simple question, but one I have never been able to forget.

I cannot speak for the other boys but I felt in him the presence of a great soul, and even to-day the recollection of it seems to give me a passport into the silent seclusion of the temple of God.

There was another old Father whom all the boys loved. This was Father Henry. He taught in the higher classes; so I did not know him well. But one thing about him I remember. He knew Bengali. He once asked Nirada, a boy in his class, the derivation of his name. Poor Nirada had so long been supremely easy in mind about himself—the derivation of his name, in particular, had never troubled him in the least; so that he was utterly unprepared to answer this question. And yet, with so many abstruse and unknown words in the dictionary, to be worsted by one’s own name would have been as ridiculous a mishap as getting run over by one’s own carriage, so Nirada unblushingly replied: “Ni—privative, rode—sun-rays; thence Nirode—that which causes an absence of the sun’s rays!”